Preface

Back in 2021, I started using Roam Research (which I’ll refer to as Roam) as my notetaking tool. In a previous article titled “Why I Use Roam,” I detailed the reasons behind this decision. In recent years, a host of new notetaking software has exploded onto the scene. This trend has sparked interest in different notetaking methods. Therefore, choosing a notetaking tool means choosing a notetaking method.

So, how can Roam or similar software be used for academic research? There are plenty of articles out there on how to use Roam, with most focusing on the card note-taking method, which emphasizes the individuality and reusability of notes. However, fews focus on using Roam for academic research. In this article, I aim to share my experience of using Roam for academic research, from notetaking through to writing articles. The key doesn’t lie in mastering the card notetaking method but in developing a suitable note framework based on one’s own research practices to closely connect notetaking with research activities.

Key Concept: Two-Stage Notetaking

Initially, notes serve to consolidate our reading and reflection. Eventually however, the notes themselves warrant further exploration, reevaluation and organization, to generate newer notes. Consequently, notetaking typically involves two stages, which I call Stage A and Stage B.

Stage A notes are the raw notes, which could be literature excerpts, reflections, or even an image or a link. In my case, Stage A notes primarily consist of literature reading notes.

Stage B notes are refined notes, representing a secondary process where notes are taken on the raw notes. In my case, I extract specific concepts or issues based on the literature reading notes or establish links between different Stage A notes.

Put simply, during academic research, I first read numerous pieces of literature and take notes. Then, based on these literature notes, I extract relevant concepts or issues for further exploration. This is a common practice across any note-taking tool, including traditional paper notes. However, Roam has improved the efficiency and elegance of this process.

Research Practices: Three Projects

Before I started using Roam, I spent a week designing a note framework tailored to my own learning and research practices. The essential point here is that you should establish a note framework according to your own studying or researching pracrices. My personal research pracrices involves regular in-depth reading of literature, reflecting on and organizing the literature, drafting fragmented thoughts, and eventually writing.

My research zeroes in on the philosophy of law, a category of humanities theoretical research. If you’re familiar with theoretical research in humanities, you’ll know that texts, authors, and concepts are three fundamental pillars of any research in humanities. Philosophical and social science theories deal with these three basic projects every day. What exactly does a classic text convey? What are the thoughts of a classic author on a concept? How should a classic concept be understood? Moreover, these three pillars are intertwined: the thoughts in a classic text revolve around particularly important concepts, and the ideas of a classic author undoubtedly involve a certain classic text and the concepts it expounds. Different authors discuss the same concepts, and so on.

Before the introduction of Roam, organizing notes around these three pillars was neither very convenient nor elegant. For instance, using traditional notetaking software meant creating many documents or pages, with linking them together for two-stage notetaking proving complex.

However, Roam solved these issuess with ease. Each note in Roam is essentially a webpage, making referencing between them as simple as creating a link. Roam even displays the links established between them. Therefore, Roam has considerably improved the convenience, efficiency, and elegance of conducting research, particularly in humanity fields.

Note Framework

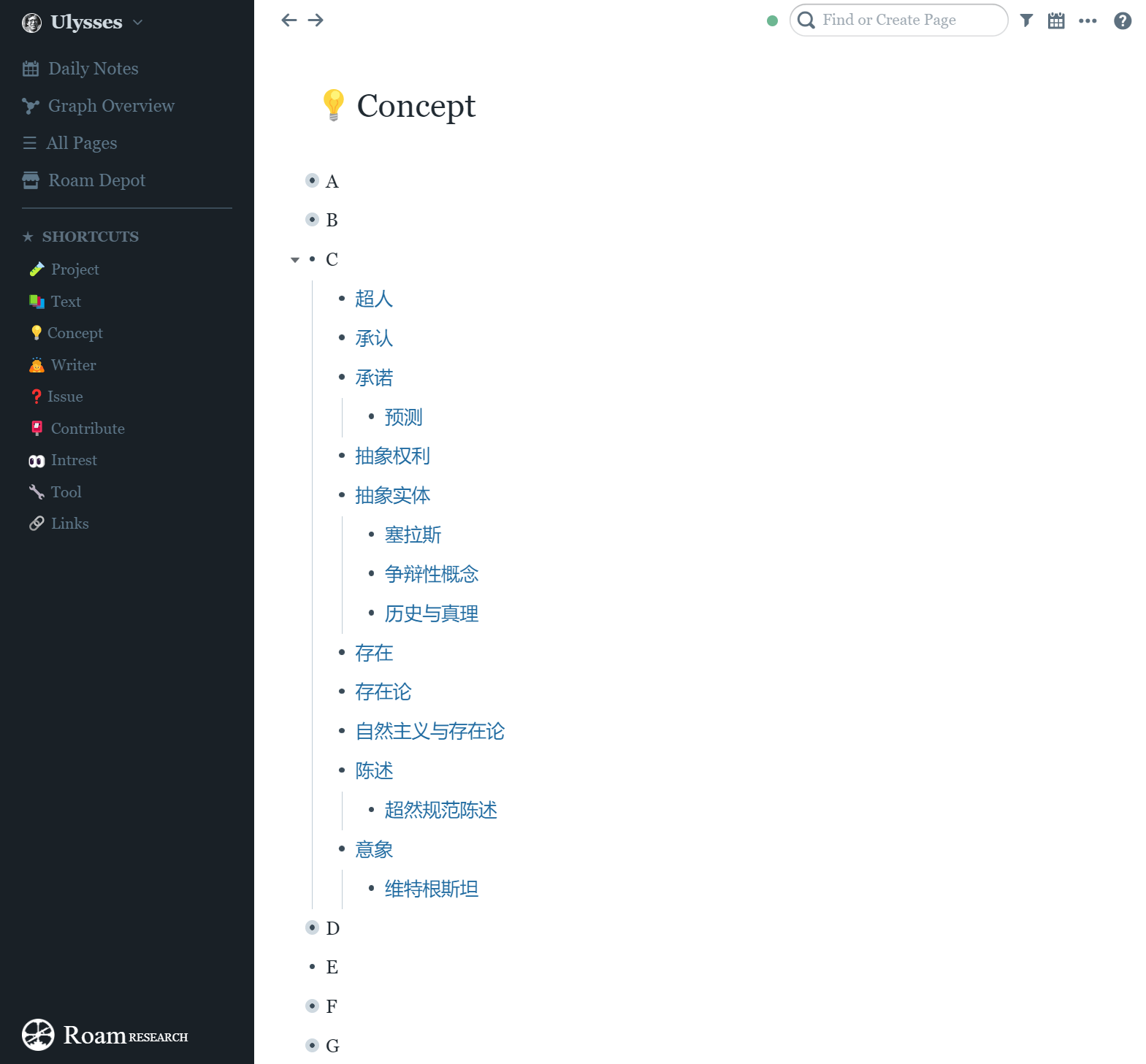

Once the research practices are clear, the note framework can be designed accordingly. Start by creating several root projects (or if you prefer, “nodes” or “pages”), namely “Texts,” “Authors,” and “Concepts.” These three projects can serve as both Stage A and Stage B notes.

Roam advocates often mention that you don’t need to care about the tree-like relationships or hierarchies between notes. Generally, this is correct. However, it’s still necessary to establish some root note projects. This is not only related to the form of note organization but also involves the essence of research practices. Roam precisely combines the form of note organization with the essence of research practices. (Of course, in my case, I also established some transactional root projects outside of core research, such as “Issues,” “Submissions,” “Projects,” “Interests,” etc. Since these are not the core issues, I won’t mention them further below.)

These root projects are typically fixed on the left sidebar of Roam. Their content is not determined all at once but changes over time. My daily note-taking process is as follows:

Add new projects in “Texts,” typically are literature that is being read or awaiting reading.

Make reading notes within these texts projects. These projects constitute Stage A notes.

At a future specific time, read Stage A notes, and open or create new projects on the right sidebar. For example, while researching Stage A notes and wanting to summarize key points or issues about a particular figure, whether it’s the author of the current text or related authors. You can also create entries for related concepts or issues. These entries will be opened on the right sidebar.

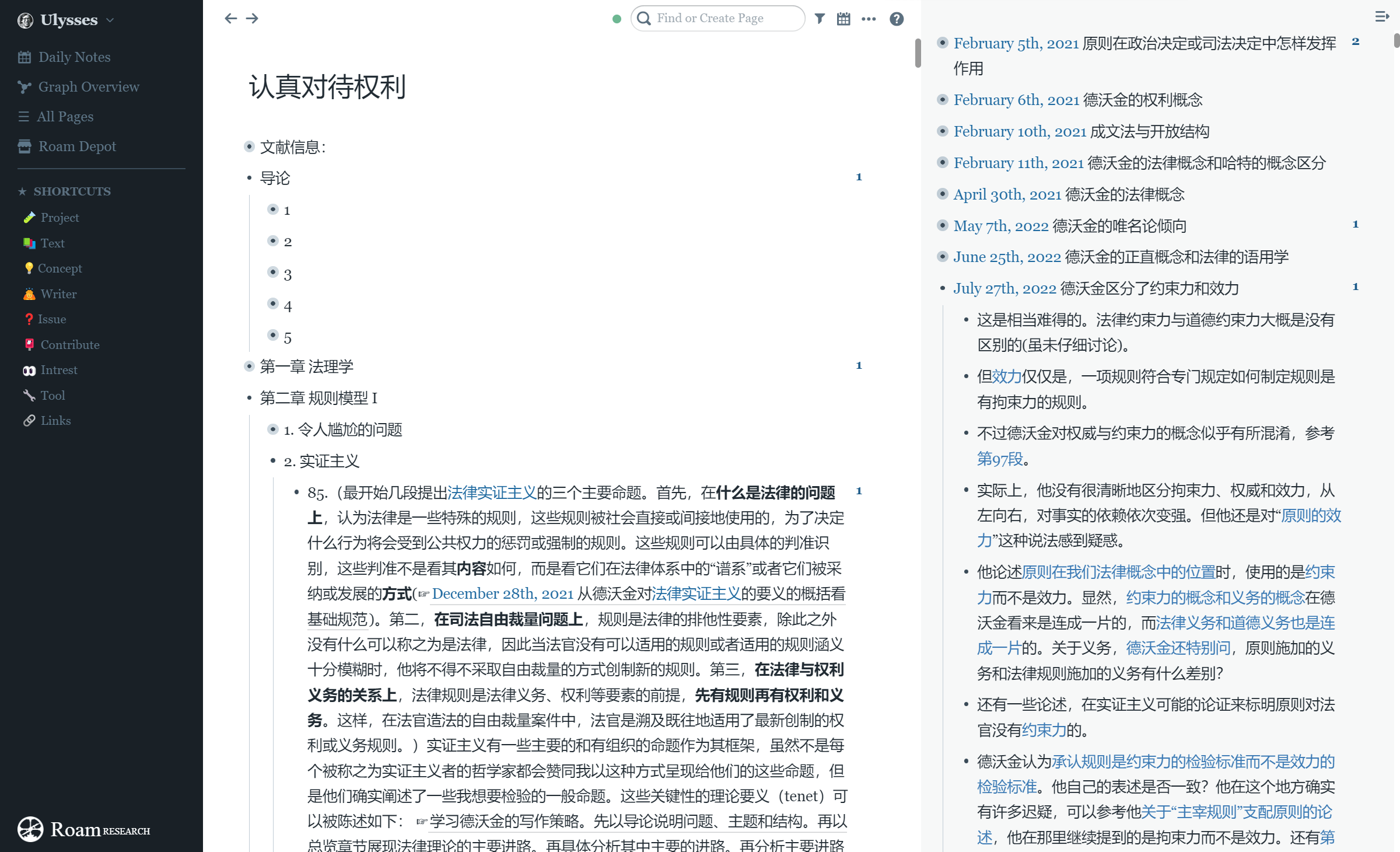

Here’s an example. As shown in the image below, the entry “Taking Rights Seriously” (《认真对待权利》authored by Dworkin) is one of my Stage A notes. When writing to a certain extent or at a specific time, I may create or open the “Dworkin”(德沃金) project on the right sidebar and then extract, organize, or summarize certain key points.

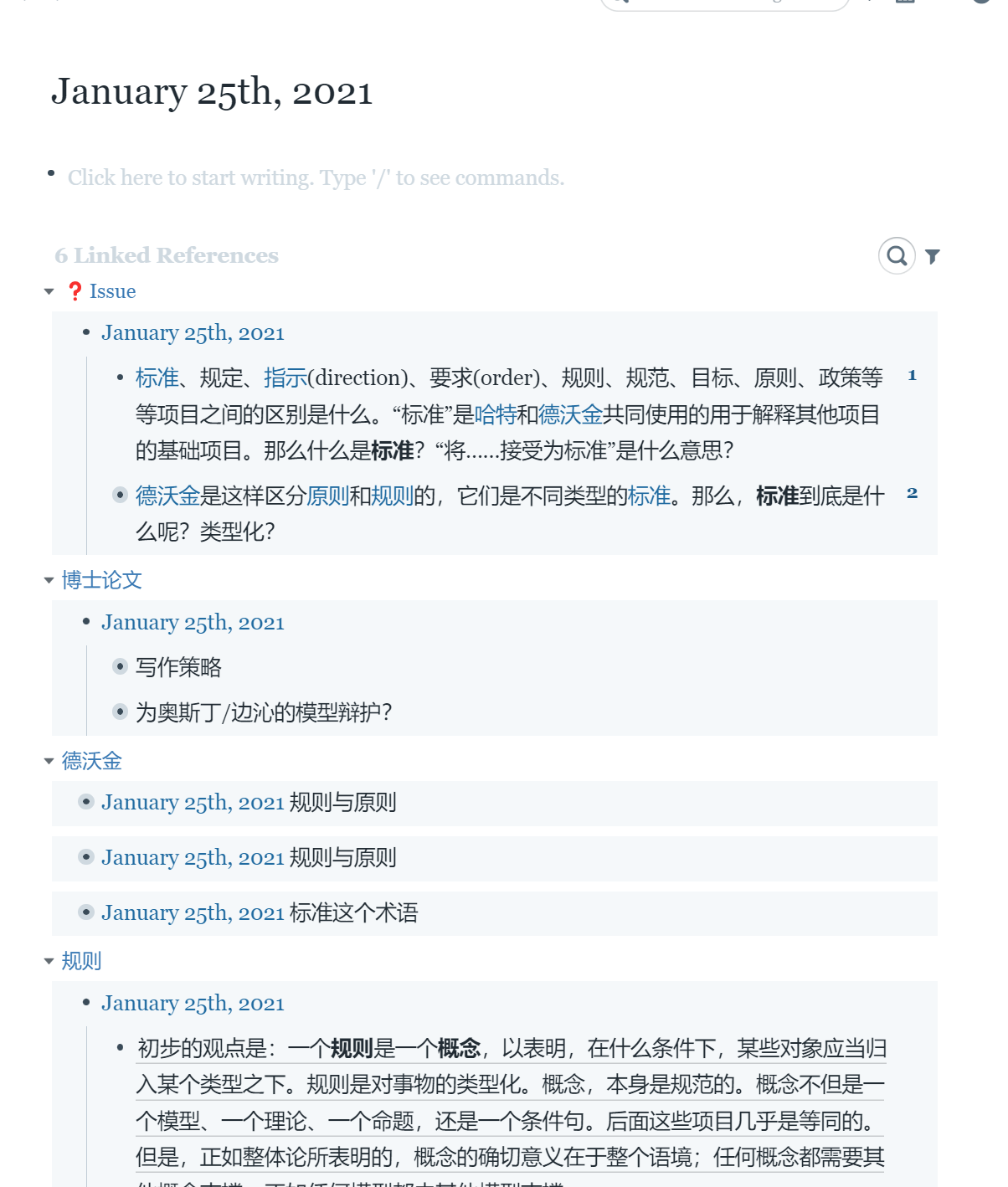

You may notice that each node within the “Dworkin” project starts with a “daily notes” node and a simple title. This is because the information we have about a author, concept, or issue, as well as the thoughts we develop based on it, are not complete or final. They undergo a process of addition, deletion, and revision. Therefore, leaving a timestamp for Stage B notes can reflect this real process. Additionally, at different times, we may contemplate and organize the same or similar issues. For example, in March of last year, I contemplated Dworkin’s views on the issues of the individualization principle of rules, based on the Stage A note “Taking Rights Seriously,” and in October of this year, I may contemplate this issues or a similar one again. Still, there’s no need to go through the “Dworkin” entry, as I can directly write a new entry. The note-taking software will record and display possible connections between them. When further organizing in the future, we can also compare thoughts from different periods.

Furthermore, notes on different issues may be taken at different times. For example, on February 2, 2022, I may have researched both Dworkin’s views on the issues of the individualization principle of rules and read Raz’s “The Concept of the Legal System,” which involves this issues. At the same time, I may have checked H.L.A Hart’s views in “The Concept of Law,” or many other issues. These issues may generate Stage B notes, and when each entry has a timestamp, opening the corresponding daily note link in the future can provide an aggregation of what research we did at some time, which is likely highly relevant.

In summary, Stage B notes involve the extraction, organization, and expansion of Stage A notes, and it’s not a one-time process. Over time, the information we have about related issues and the thinking process will change. Roam helps us reflect this process.

It can be seen that literature notes in the root project “Texts” are usually Stage A notes, while notes in the root projects “Authors,” “Concepts,” or “Issues” are usually Stage B notes. One small trick is that during the process of creating a concept list, if entering a concept in ”[[]]” doesn’t prompt a selection, then it’s a new concept. In this case, it needs to be added to “Concepts.” Also, for added convenience in adding and retrieving, both “Authors” and “Concepts” are organized in order of letters in an alphabet. The concept list aims to be concise, and maintaining such a list may not seem useful in daily, but it’s a process of building one’s own knowledge system and network.

From Notes to Writing

We already have two stages of notes. Stage A notes are generally used for the material of Stage B notes (we may also reference Stage A notes extensively in Roam’s Stage B notes), and they can also be used as material for future writing. Meanwhile, Stage B is mainly used for future thinking and writing. For example, we may already have a lot of content for the “Recognition Rules” in Stage B notes. If you want to research this concept, you can open this project and explore all the Stage A or Stage B notes associated with it.

How to realize the process from notes to writing in Roam? The key is to do a good job with the two stages of notes. The better you do with Stage B notes, the more convenient your future writing will be. In my case, I often write many lengthy thoughts in Stage B. Sometimes in the process of taking notes, some ideas are very novel or deep for a certain issues, and unconsciously, I write a lot. So, I simply create a new writing project in the “Projects” root directory and expand it into a blog post, even into an academic paper.

Here, the key is not the so-called card note-takeing method. All you need to understand is that according to such a designed note framework, Stage B notes are not only able to connect with Stage A notes and other Stage B notes, but also can be repeatedly used, arranged or modified in future note-taking and writing. If you want to call these Stage B notes “card notes” or “permanent notes”, there’s no problem.

Technical Issue: Writing Papers on Roam

Many people believe that Roam is only suitable for note-taking and drafting short articles. How do we go about it if we want to write a paper in Roam? Can Roam’s outline editor handle this task? Yes. Over the past years, from writing few paragraphs to writing blogs and papers, I have done all on Roam.

Firstly, for writing with simple formatting requirements, Roam can export any node as a Flat Markdown document. For those who rely on the outline editor to think and write more orderly, writing on Roam is a vital need. Of course, if you don’t have such dependence, the rest of this section is unnecessary to read.

Secondly, Roam still can handle writing with complex formatting requirements, but with the help of LaTex. LaTex fits any text editor, including Roam’s outline editor. With appropriate markings, LaTex can generate a paper with complete format upon compilation.

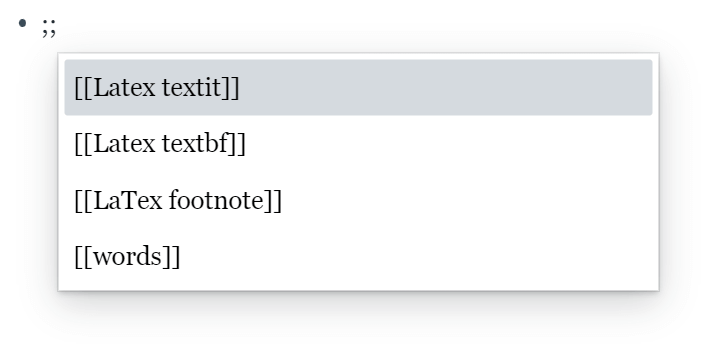

Common LaTex markings are “\footnote{}”, “\textbf{}”, and “\textit{}”. For images, lists, or tables, I suggest leaving corresponding markers when editing on Roam, and adding them later in the specialized LaTex editor. On Roam, you only need to write the main text and don’t need to add full LaTex markings. Using the template feature Roam provides, you can easily call up commonly used LaTex markings, as shown in the figure below.

In this way, write the main part of the paper in Roam, along with necessary LaTex markings. When finished, export it as a Flat Markdown document and continue to edit in a specialized LaTeX editor.

Maybe your tutor asks you to submit a Word document for review. A convenient way to convert Tex documents to Word documents is required. Pandoc offers can heplp you. Firstly, use Pandoc to prepare a Word document template and then use Mricosoft Word program to adjust the formatting of this document template to the format required for the paper. Then, use Pandoc commands to convert the Tex document to a Word document. Since it is not for official paper submissions, Word templates don’t need to perfectly match the paper formatting requirements. Of course, theoretically, Tex documents can be converted directly to Word documents without further formatting adjustments, as long as you’re willing to spend enough time adjusting the templates and Pandoc commands. This technical detail is not the main topic of this article, and I will elaborate it in another article if possible.

Summary

This article outlines how to do academic research on Roam, using the author’s own study and research practices as examples:

First, the basic issues of note-taking should be established: two-stage notes should be created, and the initial notes should be organized and digested for further thinking and writing in the future.

Second, establish a note-taking framework in accordance with your specific study and research practices. The note-taking framework is the basic root directory on the basis of which all notes are organized, and the process is also a research process.

Third, by taking good two-stage notes, you will be able to realize the process from notes to writing.

Finally, in order to be able to complete the research and writing process on Roam for complex issuess, other technological tools such as LaTex, Pandoc are needed.

In conclusion, we should establish a note-taking framework, take good two-stage notes, and use the notes for writing based on a clear understanding of our own learning and research practices.